Thinking of the Future

A Love Story

Book Publication

Preface

I CREATED MY SELF-PORTRAITS IN 1996, two years after my husband’s death.

He had died unexpectedly on our vacation in the Swiss Alps. His death left me utterly devastated and lost. Back in New York City, whenever the phone rang, I expected to hear his voice at the end of the line. Whenever I walked to familiar surroundings in my neighborhood, I felt his presence. My pain seemed to increase with time.

One day it struck me that I had to confront my grief as a photographer and artist. Doing so, I sensed, would be deeply cathartic.

I went into seclusion for extended periods of time. My task required absolute solitude, without the help of an assistant. I took detailed notes for possible images; I practiced using tripods in a confined space, mirrors, backdrops, various fabrics, and a 60-foot camera cable release. Despite my detailed notes, I was never quite sure what might happen artistically on a given day. Sometimes my imagination unnerved me. I seemed to be stepping outside my own body – physically, mentally, and spiritually – as if observing myself. The nude portraits are a reflection of my vulnerability at the time. Without my husband I had no foundation. I was floating in space.

Essay by Claudia Steinberg

GRIEF IS A VAST SPACE, reaching far beyond the horizon. Even after wandering through this enormous barren landscape for two years following the death of her husband, Carin Drechsler-Marx cannot make out its contour: on the contrary, it just seems to become more immense with every step. A space where, as Inger Christensen said, “the silence has doors everywhere.” So one day the widow, fifty-seven-years old at the time, realizes that in order to contain this terrifying expanse of loss and loneliness she has to capture it with the only weapon she has – her camera. To take her grief prisoner in her quiet New York apartment, to get to know it intimately by exposing herself to it: completely naked, showing her wounds — she herself would become its mirror.

-

Carin Drechsler-Marx arrived in New York in November of 1960 and eventually picked up a camera, slowly conquering the monumental city that made her feel so insignificant by confronting it on her own terms. Her childhood in France and Germany had been scripted by the war, and there existed hardly any photographs documenting her family during its restless flight through Europe. There was, however, a lone, framed picture of her father, who had been killed in an explosion near the Eastern Front. As a child, Carin stared at it so many times, but the man in uniform was to remain an enigma for her entire life. Obscured by the fog of trauma, her early years barely yielded any internal images either. Her first memory, imprinted around the age of six, is a tiny film snippet of black, steaming locomotives passing through the Czech Duchy of Tetschen where Carin’s paternal grandfather was stationmaster; that image of perpetual arrival and departure seems to distill her peripatetic beginnings. More than twenty years later, a world apart from that provincial station, Carin celebrated her marriage to the German-Jewish émigré Henry Marx at the Metropolitan Club on Fifth Avenue — a modern bride in a white, Chanel-inspired dress and white opera gloves, with a one-year-old baby at home in Greenwich Village. No rings were exchanged, and not a single photograph memorialized the event.

But there is a picture of the couple, taken in 1986 by their daughter Katina that Carin chooses as a stand-in for their relationship and as the leitmotif of her project. Carin faces the camera with a slight smile and proud glance, while Henry seems to be gazing at her, his eyes and their focus slightly obscured by his glasses. She has put both arms around his neck, holding on to him with her clasped, bejeweled hands resting on his shoulder in a possessive, inescapable embrace. And yet, he did slip away, as they knew all along that he would. The man who had seduced Carin with poems by Goethe and Schiller proposed to her with a cool calculation: “If I die, according to the average life expectancy for a male, at the age of eighty-two, you will become a widow with fifty-five.” They would have twenty-seven years together — at the start, it seemed like a long time.

Dylan Thomas called grief a “thief of time.” When Henry dies, eerily correct in his prediction, on a gorgeous day in the Swiss Alps, grief steals Carin’s future and her present and it also claws at the past, contaminating all that was once joy with raw pain. Everything is grey, and so her photographs have to be in black & white: “One cannot mourn in color,” she says. The first image of her series shows her in retreat from the thief, hiding her head under the delicate handkerchief Henry had given her early in his courtship. Her downcast eyes are almost visible under the veil with her embroidered initial, signaling that it is she, Carin, underneath. Then, like a priestess in a dark gown that fuses completely with the black background and wearing a silver shield on her chest, she holds up a portrait of Henry in front of her face, obliterating her own. The following three images show her under layers of sheer black fabric, still invisible except for the last one, where she carefully, reluctantly, reveals just one sad, watchful eye. Only to hide her face behind a bouquet of roses in the next picture.

Henry hardly ever brought her flowers – his gifts were mostly pieces of American Indian jewelry, talismans of their shared fascination with the native culture of their new home country. But flowers belong to the traditional vocabulary of mourning, the language of vanitas, which Carin adopted while finding her own insignia of sorrow: slowly, reluctantly she emerges from her protective textile screens, exposing her legs, parts of her belly and breasts, and finally her shoulders and wide eyes that stare at the lens – a creature caught in her cave, an unwanted light exposing her while a heavy weight of darkness continues to press onto her crouched, naked body from above. Further on, she lies down in the midst of a magical frame composed of copies of the iconic double-portrait of Henry and herself, floating within the borders of that sacred space — almost a classic sleeping nude if it wasn’t for her shoulders, so tense from the yoke of grief.

Maybe it is not just the loss of the beloved partner that has inscribed itself onto Carin’s body — this beautiful, strong back she presents trustingly to the camera has also carried many other burdens: the displacements, the starvation and the cruelties of her childhood; the despair she witnessed in her mother, a widow with four children at twenty-eight; the disappearance of her father, whose forced or voluntary entry (she will never know) into the Waffen SS casts a shadow over her biography. After the war, Carin’s mother instructs her to never mention to anybody her father’s membership in the now reviled elite group, and the ominous cloud of secrecy and incomprehension fills the vacuum of his memory like a poison. To protect her mother, the little girl instinctively forgoes any questions. When the prisoners of war slowly return to the hamlet in Southern Germany where her family had found a home, she envies the other children for having their fathers back, no matter how impaired.

At age nineteen, on the way to the theater, Carin met Henry in Munich. Slowly she recognized him as her soul mate as well as her opposite: born in Brussels in 1911 in a three-story house with a marble stairway on rue Jourdan 76 as the only child of a successful German Jewish businessman and a mother who would die when he was only four, Henry grew up in a sophisticated environment, cared for by governesses. Though the two world wars dictated his moves and led him to enter the United States as a refugee, the world of books and theatre had always been his true home. He was the first man Carin ever met who drank chocolate, who took her to elegant restaurants where a phalanx of over-attentive waiters scared away her appetite. He was the first Jew she ever knew, and of the Jews and the Holocaust she had known next to nothing. Still, they had formative experiences in common: each had lost a parent at age four, and both had been in a concentration camp. She had studied to become an actress and thus shared his love for the theater – Henry later played a leading role in bringing major German theater productions to New York, and the couple’s evenings were filled with exquisite drama. When Henry became the editor-in-chief of the German-Jewish newspaper Aufbau, the most important voice of German-Jewish exiles in the United States, in the 1980s, conversations about the Holocaust would mark the end of every single day. And when Carin cooked dinner for survivors, the topic inevitably appeared at the table.

For the center images of her project, Carin pulls the ground from underneath her feet and dives naked into the liquid reflection of a shiny photographic foil – in one picture, she stretches out her arms like the wings of a bird but remains tied to the ground, as if crucified. In another she beholds her body’s slightly distorted mirror image, not enthralled like Narcissus, but rather contemplating the solitary shape and infinity below. A third one finds her in an embryonic coil, as if avoiding the glare from the light puddles around her, floating upside down, lost to the world.

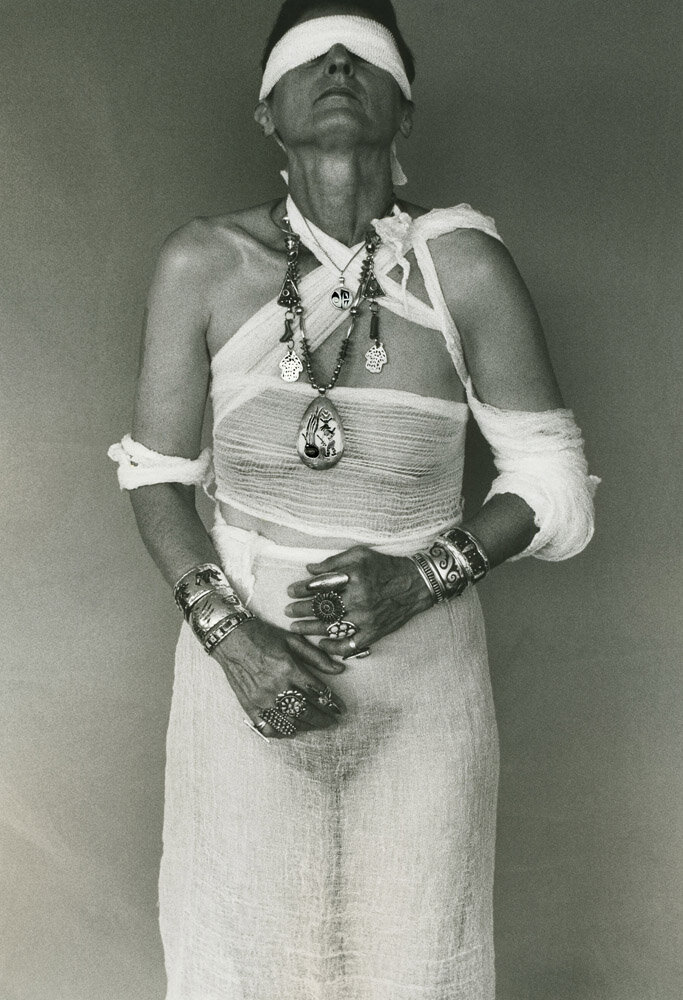

These images are radically, almost unbearably personal, and no other place than the apartment where Henry’s presence can still be felt, however lightly, would have elicited the same sense of entrapment, of isolation — and belonging. Nowhere else but here, twenty floors above Broadway and so close to the sky, higher than all the neighboring buildings, could she forge her all too familiar pain into authentic metaphors. Like her intertwined fingers tied with string so tightly as to defy any attempt of escape. Or her blindfolded face and bandaged body, adorned with jewelry as if prepared for ritual or burial. Something searching remains palpable in these self-inflicted poses, acted out without an audience and without feedback beyond her own interior sense of vulnerability – underneath the gauze, behind the veil, naked.

In the end, Carin looks into the camera defiantly, standing in front of a wall covered with numbers — the fateful dates of her and Henry’s life. He ascribed great meaning to their repetition, lending a sense of order within the turbulence. And indeed his death occurred, with striking accuracy, within his very personal, mystical numerical system. In the summer of 1994, the couple left New York to visit the remnants of the Oranienburg concentration camp where Henry had been detained after his arrest by the Gestapo on June 22, 1934. Only a plaque and the gravestone of Erich Mühsam, whose corpse Henry was ordered to cut from the gallows, served as reminders of the cruel events that happened on that site. For Henry, confronting the eradication of a reality that had influenced his entire being was perhaps a form of death. He died suddenly five days later, on June 22, 1994. And so the very last image is a repetition of the first, but this time all the features are wiped out and nothing but a shadow remains.

While Henry found peace in the precise mathematics of his fate, Carin turned to photography as a medium of mining and making memories, documenting her emotions through symbolic gestures. She gave these states of fragility and desolation an intense gestalt, anchoring them in time. From that anchored spot, the elusive edge of grief finally comes into view.

Henry - Carin

Carin - Henry

The Day We Met

I VIVIDLY REMEMBER THE CHILLY WINTER EVENING: January 17, 1959. Only three weeks before I had moved to Munich from a sleepy, medieval city in southern Germany. I was nineteen years old. At the time my ambition was to become an actress, my true calling, as I believed then. I worked in a Certified Public Accountant’s office during the day, and evenings I took lessons at a private acting school.

-

On that particular evening, I was made up in a pink, embroidered, tight-fitting dress, black high-heeled shoes, and a gray, herring bone coat. I was on my way to Calderon de la Barca’s La Dama Duende at the enchanting Cuvilliés Theater. New to Munich and unaware that I was only a few steps from the Cuvilliés, I asked a passer-by for directions. “In that case we can lose our way together,” Mr. Marx, who was on a short visit from New York, said smilingly. He himself was on the way to the Cuvilliés. Before we took our seats — his way up front in the orchestra, mine in the top balcony — he asked whether we could meet during the intermission. Reluctantly I agreed. Our destiny was sealed. La Dama Duende was the prelude to our lives together.

Initially, I would have gladly shaken off this elderly gentleman. Nothing was further from my mind than getting involved with someone 27 years my senior. Not in my wildest dreams did I imagine that, one day, Mr. Marx would become the love of my life. He was persistent, called me at work repeatedly, until I finally gave in to meet him - at a restaurant or the theater. As it turned out, he happened to be a theater and music critic for the German language paper Staats-Zeitung & Herold in New York. Whenever he returned to Munich in the following months, indeed until his death, the theater remained for us the quintessence of our first encounter.

In Common

SOON WE DISCOVERED THAT WE had a number of things in common. We were both born in French-speaking countries: Henry in Belgium; I in France. We had both lost one parent at age four: Henry his mother, I my father. And we had both experienced concentration camp internment, though completely different reasons.

-

When we met in January 1959, Henry was the first Jew I had ever met. I knew next to nothing about the Nazi era and the Holocaust. Germans were not yet willing to confront their most recent past; neither parents nor teachers nor public figures spoke about the horrendous events.

“This is the site of the Brown House*,” Henry pointed to a place on Brienner Strasse at Königsplatz on one of our first walks through Munich. He was astonished at my naïve question about what the Brown House had been. A few days later, as a participant at the TV show Frühschoppen in Cologne, he talked about his meeting a young German who knew next to nothing about the Nazi era and the Holocaust. I was mortified.

From that time on, I asked myself countless times what kind of a man my father had been, and what crimes he may have committed during the time he belonged to the Waffen-SS. Tormenting questions for years to come, especially in view of the one human being that I loved more than anyone, the one who returned my love with utmost affection.

*In 1931 the “Brown House” became the headquarters of the Nazi party; the term “Brown House” referred to the color of the party members’ uniforms.

No Wedding Rings

OUR MUTUAL JOURNEY HAD TAKEN eight long years of platonic love, yearning, doubts, separation, and finding one another again. On October 6, 1967, at last we were able to marry. Long before that day we had decided against wedding rings. There was no need to proof to the outside world that, now, we were husband and wife. Though, by us not wearing wedding rings, people often seemed to question whether we were father and daughter, or even whether I was my husband’s young mistress. In the beginning such puzzling looks irritated me, but, as time went by, I found it amusing.

No Flowers, but Jewelry

I EASILY CAN COUNT ON ONE HAND the number of flower bouquets Henry ever gave me. One of those rare instances took place in Tokyo in 1968, when we accompanied the Vienna Burgtheater on their Japan tour. Of all the places in the world, there, to my delight, Henry surprised me one morning with a small bouquet of primroses. He preferred to show his affection with jewelry anywhere at any time. Mostly his taste was impeccable. He knew that I favored silver jewelry, especially ethnic jewelry, to gold and precious stones. On his way home from a busy work day, he may pass a jewelry store, notice a ring or bracelet that he thought would please me, and bought it on the spot.

-

Traveling in Marrakech in 1981, we stopped at a small shopkeeper’s place. The owner praised his embroidered handbags and cushions. But we were intrigued by a stunning Berber necklace with large, round silver beads and a rectangular, inlaid silver pendant. The pendant contained a passage from the Quran. The shopkeeper expected Henry to bargain. Not accustomed to bargaining and sweating profusely in soaring temperatures, Henry simply paid the asking price – to the delight and disappointment of the shopkeeper.

We both felt a strong connection with the culture of Native Americans and frequently traveled to the Southwest. My collection of Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni jewelry grew from year to year. Not a day goes by without my wearing one of those unique pieces. They are more than jewelry to me. They radiate the Native and, deep down, Henry’s spirit.

Numbers

HE HAD AN ALMOST MYSTIC RELATIONSHIP to numbers and a phenomenal memory.

Before entering a hotel room on our many trips (to Europe, Japan, Turkey, Morocco, Israel, etc.), he glanced at the room number, and without fail would find a connection to a unique personal date.

He was able to instantly recall historical dates, as well as birth and death dates of famous people. Every April 20th he shouted with sarcasm, “Today is Hitler’s birthday.” He basked in his ability to add or multiply complicated figures in his head. No one even attempted to prove him wrong.

-

“You are not too young for me,” he wrote in one of his early letters to me. "Whether I am too old for you, of course, only you can decide. According to actuary tables, and assuming that I stay healthy, I should expect to reach an age of eighty, maybe even a few years more. This would mean that when you are about fifty-five, you will have to continue life without me. Does that frighten you?”

Back then, such thoughts were far from my mind. I was twenty-one years old, at the beginning of my adult life. Our age difference barely seemed to matter. The actual moment when I had to continue my life without him indeed came just a few weeks after my fifty-fifth birthday.

Was it coincidence or providence that he was 27 years my senior, that I gave birth to our daughter at age 27, and that we were married for 27 years?

Henry - Carin

Henry’s Parents’ Home

I NOT ONLY LIVED IN my parents’ home, I was also born there in 1911.

My parents’ home was and still is in the Brussels district of St. Gilles, rue Jourdan, 76. It is a three-story, narrow building, customary in a country with a window tax. The kitchen was in the basement. From there, a long, white marble stairway led to the living and dining room. I vividly remember falling down the sixteen stairs once, ending up with so many scratches and open wounds that I would not have been able to count them, if I had been able to count.

-

The house was beautiful, with lots of space and a large backyard – a place an only child liked best. There I could drive around on my tricycle, dig in the soil, and keep my playmate, a turtle. The turtle and I were inseparable. Late in the fall, however, it dug itself into the ground to hibernate until spring; with the first warm rays of sunshine, it reappeared like clockwork. But in the year after my mother’s death, the turtle did not return. The five-year-old boy was inconsolable und could not understand why the turtle had left him. I believe I cried harder over the loss of my turtle than over the death of my mother eight months earlier, which I was not yet able to cope with rationally.

Thus, my parents’ home became my father’s home. My mother had been ill for a long time: she suffered from pernicious anemia, which also afflicted her three older sisters. At the time, there was no cure; a few years later, patients were effectively treated with raw liver therapy and synthesized vitamin B. Two sisters, who were born before me, died as infants, also victims of progressive anemia and insufficient renewal of blood platelets, an illness that is often transmitted from mother to daughter. As I was told later, my mother did not want to die without a descendant; her wish could only come true if she were to give birth to a boy.

She took the risk – and so I was born: weak, anemic, with a heart defect, but viable. I suffered from colds and bronchitis countless times in the foggy winter weather of Brussels, and was not permitted to go outside before 11 a.m., even in my first school year.

My father owned several furniture stores in the South of Belgium, near the French border, where he lived during the week. Since my ill mother was hardly able to take care of me, I was looked after by a succession of nannies or governesses.

I was not yet three years old when World War I began, but the war became bitter reality for me only after it ended on November 11, 1918. I was seven then, and the war gripped me no less than the young Goethe who was the same age at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War. As my father, who originated from Baden, Germany, had never applied for Belgian citizenship, it seemed advisable to leave Belgium as fast as possible. Thus, we left for Cologne by train on October 30, 1918. The train was packed with German soldiers, carrying their knapsacks and carbines as they returned from the collapsing front in France. Until then I had been far too protected to understand the meaning of war, but now, seeing the dirty, unshaven, and tired soldiers and their weapons, it dawned on me. And I realized something else on this trip: I had grown up in a French environment, and was now catapulted into German surroundings. I would have to learn a language of which I understood barely a few words.

I didn’t have the slightest inkling then that this was the beginning of years of travel. Only after four places of residence, seven apartments, and four schools, did I find a true home in Berlin. For two years, from the end of 1918 until 1920, my parents' home was one hotel room after another, first in Wimpfen, then in Heilbronn at the Neckar, followed by two furnished apartments in Munich. From there we moved to a furnished apartment in Berlin until, at last, my father remarried in 1928, and we were able to live in a home with our own furniture.

These were restless years. They caused me – against my will – to grow up faster than would have been the case otherwise. Adjusting to school in an initially foreign language was not easy, especially on account of the insufficient number of teachers immediately after the war. Our “teacher” obviously was a disciplinarian who had come back from retirement. He didn’t miss any opportunity to maltreat us seven-year-olds with Tatzen, a South German custom of striking the inside of the left hand of disobedient students. There were other kinds of sadism in the class room, like bashing the heads of two students or pulling their earlobes for speaking without permission. Whenever I, the foreigner, who seemed to share the responsibility for the defeat of Germany, didn’t immediately understand something, the rage of this fine specimen of a democratic schoolmaster showed no mercy. I rebelled, and was moved to another school with a kind teacher. As a result, for the first and only time in my school career, I became top of the class (and received twenty Deutschmarks from an old aunt who had promised me that amount if I achieved my goal).

Around that time I received my first telephone call. It was from my father who, as in Brussels, was still on the move more than at home. I ran to the phone attached to a wall, and had difficulty understanding the voice coming from 300 kilometers distant. I yelled into the receiver, hoping this happened on the other side as well. But the voice came and went, from louder to weaker, making me feel terribly frustrated. My first telephone adventure was truly disappointing.

In the summer of 1921, I went for my first car ride from Munich to Garmisch, in an open car on a mostly unpaved road. We had to wear a tight leather coat and dust goggles, but even so I arrived totally dirty, with a dry mouth, at our destination about three hours later. Still, it was much better than a train ride, notwithstanding my motion sickness, on account of which the car had to be stopped several times.

About one year later, I received my first radio, a detector apparatus that required a needle contact with a crystal. As with the telephone, the sound fluctuated enormously; one had to reconnect the needle with the crystal again and again. Yet, to listen on a headphone, not merely to words, as on the telephone, but to music, was a miracle and made the tribulation more than worthwhile.

Approximately the same time, I saw my first black-and-white, silent movie: it was about the second expedition to the South Pole by the British explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton.

While I cannot remember hearing music from a gramophone for the first time, I vividly remember my first television broadcast. During the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936, some of the contests at the Olympic Stadium were broadcast directly to a kiosk at the Potsdamer Platz. Likewise, I clearly remember my first flight: on board a DC-3 in April 1937, from Miami to Havana and back, where I received my immigrant visa for the United States.

Next to the technical achievements, I witnessed the political developments with heightened awareness. In Munich, where I lived from 1920 to 1926, I became an eyewitness to the shoot-out that squashed the Hitler Putsch at the Odeonsplatz. On that particular day, November 9, 1923, we students were dismissed after the second or third class without being told why. I went to my usual train stop to get to Goetheplatz, but no train came. I had to walk. But because the police had cordoned off all streets in one direction, I walked in the opposite direction, and arrived at the Odeonsplatz precisely at the moment when the police began shooting at the Nazi demonstrators. I saw several men fall, others ran away, and I also ran quickly past the Odeonsplatz to the Briennerstrasse, the Maximiliansplatz and, via Lenbachplatz, Stachus, Sonnen- and Lindwurmstrasse, to my home that I usually reached by tram in no time. The next day I read in the Münchner Neusten what I had witnessed unaware.

At this time I was also not aware of pronounced anti-Semitism at my school. But there were a number of teachers who made no bones about their sentiments. At best they were honest conservatives and decent pedagogues, who at least treated all students equally, but they did not try to establish a counterweight to the ruthless Nazis among their colleagues. On the other hand, we had a Jewish teacher by the name of Schaalmann, who was extremely strict with Jewish students to avoid any reproach of partisanship. On account of him, mathematics was torture for the rest of my school days and, unfortunately, also beyond.

Luckily I could retreat from such hardships into the world of books. At the time we were subtenants of a furnished apartment near the Bavariaring. A huge bookcase, filled with books from top to bottom, was part of the furniture. Now, to my heart’s delight, a large selection of books awaited me. Before I had only read books for children and adolescents; now I could read literature reserved for adults. I failed to understand much of it at first. But strangely enough, the more I read, the more sense it made to me. For the first time I was introduced to Heinrich Mann, Arnold Zweig, and Jack London. I read Goethe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit (Poetry and Truth), but also fiction. It was, if you will, a very eclectic bookcase. Since that time I have never been without books; sometimes they took up more space in my home than was agreeable to the rest of the family. Eventually I discovered something else: chess. Sometimes I played with a partner, but often by myself. I eagerly replayed chess tournaments, published in the Einkehr, a regular supplement of the Münchner Neuesten, and I learned the opening and gambits of such chess masters as Lasker, Tarrasch, Marshall, Capablanc, and Aljechin. It was several years before my chess fever subsided.

Life in Munich ended faster than I expected, because my father, a partner in a real estate business, was transferred to Berlin. The leap from Munich to Berlin plunged me into a crisis more difficult to overcome than the compulsory relocation to New York a decade later. I arrived at the capital of Prussia as a Bavarian: I spoke German with a Bavarian accent, and my way of thinking was slower than that of the fast-thinking Prussians, whose dialect I often didn’t understand right away. My classmates made fun of the immigrant, and the teachers joined the cruel game. Again I had to defend myself against a hostile school environment, as I had had to do twice before. The fact that, two years later, in the Oberprima (equivalent to senior high school), I was elected class representative shows how well I dealt with the situation this time.

What seemed unattainable during two years in Heilbronn and six years in Munich, I accomplished in Berlin within six months: I had found a new, the only Heimat of my youth. I felt like a Berliner. I plunged into the intellectual and artistic life near the final phase of the Weimar culture, ventured into my first literary attempts (to the chagrin of the principal who also taught the German class), and I studied for four years at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University until the Nazis made any further development impossible. After these painful, prematurely terminated studies, I began an apprenticeship at a bank. That also came to a quick end, when, in June 1934, the Gestapo gravely threatened my external and inner existence, and forced me to view life from the perspective of two concentration camps: Oranienburg and Lichtenburg.

Fifty years later, I would be lying to claim that I had been prepared for such events. In hindsight I can only say that these events cut a deep wound, ending the period of naïve youth. Only much later did I understand the truth behind Nietzsche’s words, “what does not kill me makes me strong.” I stayed in Berlin for two more years, before I bid farewell to the remains of my parents’ home in January 1937, in order to immerse myself in a new world – the new world of America. My stay there turned out to be the longest in my life.

But my intellectual roots took hold in my Berlin years. I bid farewell in the awareness that – like Heinrich Heine a century before – no one could take away from me the other: the portable Fatherland.

Henry Marx: Excerpts from ‘Mein Elternhaus’ – My Parents‘ Home

Ein deutsches Familienalbum (A German Family Album)

©1984 Econ Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf and Vienna

Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, München, 1986 (Translation Carin Drechsler-Marx)

Childhood Memories

ON THAT FROSTY WINTER NIGHT, when our paths crossed for the first time, Mr. Marx suggested we go to a nearby café at the end of Calderon de la Barca’s La Dama Duende.

I was astonished that, next to mouthwatering pastries, a gentleman his age would order hot chocolate and not coffee, like me. He asked about my life and my family background. He listened intently, now and then interrupting with more questions. Though shy by nature, I sensed that I could confide in Mr. Marx without hesitation. For the first time in my life, someone really listened to me.

-

I told him that for much of my childhood my family had been on the move from city to city, from country to country. I told him that my father had been a member of the Waffen-SS and that, as a result, my mother and her children were imprisoned at the Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsace. When Mr. Marx returned to New York City two weeks later, he knew in detail of the painful Drechsler family history. He in turn had recounted his horrific ordeal of persecution under the Nazi regime. Only years later was I able to fully comprehend how mercilessly our journeys were intertwined by history.

My mother and father had left their homeland in Czechoslovakia in 1936, after the birth of Monika, their first child. They went to Strasbourg, France, where my father, a chemical engineer, worked for a French-Swiss paper manufacturing company. I was born in Strasbourg, as were my two younger brothers, Roland and Michael. Every year one or two of us children stayed with either set of grandparents in Czechoslovakia for a couple of weeks.

After Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland in September 1938, my parents had to apply for German passports. They were now German citizens living in France. With the start of World War II, my father, now an enemy alien, was arrested by the French and interned in Libourne; my mother took refuge with us children in Switzerland. When Germany invaded France in May 1940, German troops freed my father; several months later, he was conscripted into military service. According to my mother, he would have preferred to serve in the Navy or Air Force, but as an expatriate German he had no choice but to join the Waffen-SS.

Stationed in Zhitomir, Ukraine, he was killed in September 1943, while on a train back to France. He had been released from duty at the front in order to resume his previous work at the Strasbourg paper mill, now essential for the Nazi war machinery. It was not meant to be. Partisans had mined the train tracks near the town of Winniza. My father was killed in the explosion; my 28-year-old mother was now a war widow with four small children, the youngest nine months old.

She stayed in Strasbourg until November 1944, shortly before the Allied forces reached the city. With a few bundles of clothing and a baby carriage we escaped across the Rhine Bridge to Kehl in Germany. From there we continued by train to Czechoslovakia to live with my maternal grandparents in Gablonz, a city famous for Bohemian glass production. But after Dresden was firebombed in February 1945, and the deep-red sky could be seen in far-away Gablonz, and as the Russian army was approaching ever closer from the East, my mother followed her father’s advice: She fled with her three oldest children for Southern Germany, reluctantly leaving her youngest son, 2-year-old Michael, in the care of her parents-in-law. It would have been arduous to travel through war-torn territory with four children, especially a small child like him.

Unknown to my mother or any of her relatives was the Allied plan to expropriate and expel millions of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Yugoslavia at the end of the war. Thus, forty of our family members fled Czechoslovakia in the mass exodus toward the end of 1945. My paternal grandparents and my little brother Michael made it to Eisleben in East Germany, where the grandparents died of typhoid fever. A Roman Catholic priest and his sister took in the orphan Michael. It wasn’t until 1948, after desperate searches, that my mother found him through the Red Cross.

In March 1945, after several days on different trains, we arrived in Southern Germany. A farmer in the village of Gaishaus reluctantly rented a room to us. Now at least we were able to get small quantities of milk, eggs, and vegetables in addition to the scarcefood from rationed food stamps.

Our stay with the farmer was short-lived. Following Germany’s defeat in World War II, the Allied forces divided Germany into four occupation zones. The area we had taken refuge in became part of the French Zone. My mother was asked to report to the French military authorities and was informed that, because my brother Roland and I were born in France, we were French citizens and, therefore, we all were to return to Strasbourg. My mother had no choice. Once in Strasbourg, she was summoned to the Deuxième Bureau, the French counterintelligence service where, I assume, my father’s membership in the Waffen-SS was brought up. The officials suggested my mother, who was fluent in German, Czech, and French, act as a French spy in Prague. They offered to return the apartment we had previously lived in at Quai de la Tuìlerie, and to hire a governess for us children. My mother, who had sacrificed her husband, was unwilling to sacrifice her children too.

Her refusal resulted in our internment, June 22, 1945, at Natzweiler-Struthof, a former Nazi concentration camp in the Vosges Mountains, about 30 miles southwest from Strasbourg. Guards with pointed guns shoved us into a barracks. The ordeal ended mid-November 1945, when freezing temperatures in the Vosgues Mountains became too risky for the prisoners, especially women and children. We were released and deported to Rastatt, Germany. Once there, my mother did not know where to go. Returning to Czechoslovakia was out of the question. There was no mail service;communication with relatives had long been broken off. My mother decided to returnto the same community in Southern Germany where we had briefly found refugeearly in 1945.

Desperately trying to find a place to stay, we were turned down again and again by the villagers. At long last, we found shelter at Spital Neutann, a lice- and flea-infested senior home in the countryside. It had its own farm so that, as far as food was concerned, we were relatively well off. My mother’s younger sister, Gerda, joined us there in April 1946 after fleeing from Czechoslovakia.

After nearly two years at the senior home, in one small room for the five of us, my mother felt it was time to move. A brisk fifteen-minute walk from the home, through a forest and past hilly meadows, lay the secluded hamlet of Bainders and the weekendhouse of a city surgeon. The only immediate neighbors were three subsistencefarmers. To shop for food, to go to school, to church, or to the railroad station required at least half an hour’s walk. My mother rented the weekend house, in which we lived for the next ten years. She earned a little money by knitting hats, mufflers, sweaters, and skirts for the families of the French occupying troops. Though marked by privation for quite some time, these years were the best in my childhood. To this very day, the bucolic hamlet Bainders and its unpretentious, down-to-earth people are Heimat to me.

However, ten years of living in isolation was more than my mother could bear. She found a secretarial job at a lawyer’s office in Ravensburg, the district town with a population of 30,000. In May 1957, when I was 18 years old, we moved to Ravensburg. I did not feel at home there. Less than two years later, I moved to Munich, the capital of Bavaria. And in November 1960, a few months after I had come of age, and to my mother’s deep regret, I left for America to follow my dream of a new, challenging, and inspiring life.

Carin’s Beginnings in New York City

MY DREAM TO STUDY ACTING in Munich was too difficult to accomplish under the circumstances. I was yearning for a change in my professional life.

But without Abitur (the German equivalent of a high school diploma), all rofessional avenues I would have loved to consider — writing, fine arts, psychology — were closed to me. On one of his visits, Henry suggested I go to America, specifically New York City, for a year or two. There, I would be able to pursue my goals with conviction and determination rather than with proof of diplomas. His wife, whom he had told of my difficult circumstances, had put forward the idea. The “Land of Golden Opportunities” began to appeal to media was young and daring. The world belonged to me.

Thus, my journey began.

-

I arrived in New York City on November 7, 1960, the day before John F. Kennedy was elected president. The four-day trip from Le Havre on the SS United States had been stormy, and I was seasick most of the time. Not for one second did it occur to me that in my luggage I brought along the German collective and my family’s Nazi legacy to a metropolis with two million Jews, among them many Holocaust survivors. Coming to terms with that legacy

would become an intrinsic part of my everyday life. The idea of going to New York for a year or two was inconceivable to me at first. I knew little about America. My first experience with this country went back to the early post-war years when my family was a grateful recipient of CARE packages. The cans of Spam, the Hershey chocolate and clothing were a blessing for us, the cigarettes for my mother in particular. My siblings and I proudly wore the windbreakers, dresses, and jeans. If they were too big, we saved them until they fit. Those things easily could have come from Henry and his first wife, for they too had participated in the CARE package campaign.

Everything in New York City was breathtaking and overwhelming: the people from every part of the globe, the likes I had never seen before; the glittering skyscrapers that I couldn’t stop gazing at in awe, while at the same time feeling reduced to a tiny speck; the incredible luxury and show of wealth along Fifth and Madison Avenues and, a few blocks north, the mind-numbing misery.

The first few months in a foreign country, far away from my family, put me to the test. Yet I was determined to persevere. I took a part-time job as an au pair and housekeeper for an Austrian-Jewish immigrant family. I worked as a salesgirl for Macy’s and as private secretary for the Dean at the Graduate School of the New School for Social Research.

Perhaps I would never have found my way to art and art school if the Austrian immigrant lady I had worked for had not been an amateur painter. Watching her paint intrigued me to try painting myself. In the fall of 1961, I quit my job with the immigrant family, and began a three-year study course of Fine Arts at the School of Visual Arts. At long last, my dream of an exhilarating challenge had come true. Next to my art studies, I worked as a part-time secretary for a German-Jewish lawyer on Wall Street and as a private secretary for a wealthy lady on Fifth Avenue.

My life was full of wonders. I continued my warm friendship with Henry. In contrast to his charismatic, energetic personality, his wife preferred a secluded life-style. She had little interest in socializing or accompanying Henry, the theater and music critic, to performances in Manhattan. Being a trained pianist, she was content with giving lessons to children at their Queens home. Thus, Henry and I often went to the theater and concerts together. We steadfastly kept our determination to remain merely close friends for a very long time, until one day the scales fell from our eyes and we realized that we were destinedfor one another: Destined to be together unconditionally and forever.

Carin - Henry - Katina

Katina

FROM THE VERY BEGINNING of our affection for one another, it was obvious that Henry saw in me his future wife, who would bear him another child that he so fervently wished for. For health reasons, his first wife had rejected any further pregnancies after the birth of their son seventeen years earlier. When I became pregnant unexpectedly, Henry was delighted. Our daughter was born December 3, 1966. We named her Katina, after the Greek actress Katina Paxinou. The name sounded beautiful, like music. Katina became the anchor in our lives. Our small family was a precious island within the island of Manhattan.

Two Threads

OUR NUCLEAR FAMILY was indeed an enchanted island in this unfathomable metropolis. The 27 years of marriage overflowed with deeply enriching personal and professional pursuits, above all with raising and watching our daughter, Katina, grow into a strong, independent, gorgeous young woman. Henry blossomed in his career as journalist, non-fiction writer, lecturer, theater organizer, and fundraiser, to name but a few of his activities. As soon as Katina entered the United Nations International School, I turned from painting to photography which soon became my profession. Every year we traveled to different countries in Europe, to visit my family in Germany, to hike in the Swiss mountains. We traveled to Turkey, Morocco, the Far East, and places in the United States and Canada. It was a happy and gratifying time.

-

However, my life with Henry weaved along two parallel, irreversible tracks: On the one hand Henry was the love of my life – a love he wholeheartedly returned. On the other hand, my father’s and my German collective Holocaust legacy were threads woven through my entire life. Precisely because of Henry, a Holocaust survivor, and my daily encounters with Jews in New York City, many of whom had escaped Nazi Germany, this legacy was an excruciating burden for me.

In 1963, during my Fine Art studies at School of Visual Arts, Sidney Tillim, my teacher for Art Appreciation and Writing, invited me to his home one Sunday afternoon. Newsweek had published an article on Hannah Arend’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. Tillim and his cigarillo-smoking wife needled me with questions on how the Nazi atrocities could have happened in a country with such great art, thinkers and philosophers. Blushing with embarrassment, I had no answer.

Eli Wiesel had published Night in 1960; Raul Hilberg The Destruction of the European Jews in 1961. In the second half of the 70’s and in the 80’s, Germany diligently confronted its Nazi past in numerous books and documentary films, many of which Henry reviewed for Aufbau, the German-Jewish weekly, and other German language papers. In 1977, Goethe House, the German Cultural Institute Henry worked for then, showed The Comedian Harmonists, and The Yellow Star: The Destruction of the Jews in Europe 1933 – 1945. In 1978, Eli Wallach and Anne Jackson starred in Diary of Anne Frank on Broadway. The Museum of Broadcasting showed the TV films Why Did You Not Stop Hitler, and The White Rose in 1983. Henry and I, sometimes together with Katina, watched all these testimonials in horror.

The most despairing and devastating indictment of Germany’s collective crimes was Claude Lanzmann’s nearly ten-hour documentary film Shoah: interviews with survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators of extermination camps in Poland.

At times I hated Germany and every German who had willingly or unwillingly participated in Nazi crimes with the total disregard for the sanctity of life. Hundreds of times I puzzled over what crimes my own father may have committed, and what kind of a man he had been in private. When my mother asked questions during his occasional home leave, he refused to answer for fear of the death penalty for breaking the required silence. My father remains an enigma to me.

My inner turmoil seemed to intensify in the last ten years of Henry’s life, when in 1985 he became Editor-in-Chief of Aufbau, the only German-Jewish paper in New York. Suddenly, he was catapulted to a new level of public recognition within the local Jewish and German-Jewish community as well as public institutions in Germany and elsewhere. We traveled to Israel, he lectured at synagogues, German TV networks interviewed him, he went on numerous lecture tours to Christian-Jewish organizations in Germany. Henry began to identify with Judaism more than he had ever done.

Our round-the-clock professional, cultural, and social pursuits were immensely gratifying. However, not one day passed without painful reference to the Holocaust, every evening, for instance, when I was eager to hear about Henry’s day. When we had Jewish - or non-Jewish - friends over for dinner, high-brow discussions accompanied sidesplitting humor. Yet, inevitably and to my dismay the Holocaust would habitually become the center of the debate. Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, or the documentary The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, or the German TV film The Wannsee Conference became part of our daily life, as did the countless German and American publications about the Nazi era that ended up on Henry’s desk for reviews.

Life with Henry was a precious gift from the Universe, in spite of the time when we almost lost one another, and in spite or because of our fateful, opposing backgrounds. Providence had given us the chance to prove love is the only answer to hatred.

End of Life

NEXT TO HIS EDITORIAL WORK at Aufbau, meetings with representatives of Jewish organizations, scholars and business people, lecture tours, radio and television interviews, Henry devoted time to his own book publications. I began to question whether he could sustain this relentless schedule. Our age difference, which had never meant much to me, now became a concern. Henry seemed to be in perfect health for his age, which he occasionally demonstrated by leaping up a flight of stairs. He never, even in the coldest weather, wore a hat, scarf, gloves, or an overcoat.

-

In December 1992, our lives changed abruptly when he fell ill with spinal AVM, a malformation of arteries and veins that can lead to complete paralysis. After losing his ability to walk, he had to undergo spinal surgery. All my worries about the future ceased to exist. We lived from day to day. Nothing was more important than helping Henry regain his health and former lifestyle. With perseverance he practiced walking on crutches in our hallway, back and forth, back and forth, and again. Nine months after his first operation, he had a relapse and had to undergo surgery again. He never gave up hope of recovery; in due time he resumed his work at Aufbau, reserving his energy solely to this task.

In the spring of 1994 we were invited by the Berlin Senate to spend a week in the capital as part of the 25th anniversary of the Visitor Program for Persecuted and Emigrated Berliners. We thought long and hard about attempting this trip, but Henry had made visible progress, and after Berlin, we would relax in the Swiss Alps.

Our stay in Berlin was enjoyable but also strenuous. Since his emigration to the United States, Henry had returned to Germany, in particular to Berlin, countless times. It will forever remain a mystery to me why he decided on this very trip to visit the site of the former concentration camp Oranienburg for the first time since his imprisonment there in 1934. A young German scholar had asked him - the only known survivor of the camp - whether he would like a car ride to Oranienburg and the nearby Sachsenhausen Memorial. Despite my concerns about Henry’s frail condition, he agreed. The next morning, as we approached the camp along a narrow, tree-lined street, the young scholar said, “This must be the road on which you were taken to Oranienburg.” Henry did not recognize the road; he had been transported in the middle of the night in a Grüne Minna (paddy wagon), and had not been able to see where they were going.

A week later, after our arrival in the Swiss Alps, he contracted a bad case of pneumonia. The village doctor urged him to go to the regional hospital immediately. The attending physicians suggested Henry extend his vacation by a week or two to give him enough time to recuperate before returning to New York. “That is out of the question,” he replied, “I have to resume my work as planned.”

When I arrived at the hospital the following morning - unsuspecting - the chief physician informed me that Henry had passed away at 9:30 a.m. from asphyxiation while his lungs were being drained. It was June 22, the very day he had been arrested by the Gestapo 60 years earlier.

Everything had happened with breathtaking speed. Less than two hours before, he had called me at our hotel. No one had attended to him yet; he felt extremely weak; could I withdraw some money from the local bank? It was our last conversation.

The alpine landscape was drenched in sunlight. At sunset the snow-covered mountain range radiated from Alpenglow. Alone in my hotel room, I strongly felt Henry’s presence. Alas, his life had come full circle.

My 75th Birthday

TO CELEBRATE MY 75TH BIRTHDAY on May 23, 2014, I felt I had to return to Strasbourg, my birthplace, and to the former concentration camp Struthof-Natzweiler, that had left such a crucial mark on my life. My siblings joined me for the occasion. The weather was picture-perfect in Strasbourg and Natzweiler, but the sunlit, serene campsite, surrounded by flowering meadows, lush-green forest, and the gentle Vosges Mountains made it difficult to imagine the atrocities committed there.

On this month-long trip there were other anniversaries: June 6 was the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Twenty years earlier, D-Day happened to be the very day Henry and I had flown from New York to Berlin on our last trip together. Then, on June 22, came the anniversary of Henry’s death, which also happened to be the anniversary of his arrest by the Gestapo, and the anniversary of my family’s imprisonment at Natzweiler (June 22, 1945). In addition, the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, opened an exhibition in Berlin commemorating the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I.

What was the deeper meaning of so many unique personal and historic dates during one single trip? Had a significant part of my life come full circle?

“In Hinduism it is a question of letting go, of returning everything to the River Ganges,” a dear New York City friend wrote me on June 22nd. “Take all your memories, let go of them, and give them back to the Universe.”

I had practiced Rinzai Zen Buddhism for a number of years. The principle of non-attachment was fundamental to spiritual growth: the principle of letting go of the past vs. clinging to it, which causes never-ending pain. “Things are as they are, they cannot be otherwise,” my Zen master often said.

I had never focused on non-attachment from my father’s painful legacy and from the collective German guilt. My friend’s compassionate words struck me like a flash of lightening. There and then, I felt completely free to let go, to return to the Universe that part of my life that, because of my deep love for Henry, had weighed me down for many years. Still, every step on my life’s journey will forever be an integral part of who I am.

Wir Denken An Die Zukunft

DU HAST MIT MIR GELITTEN,

hast dich mit mir gefreut.

Du ließest dich nie bitten,

hast keinen Weg gescheut.

NIE KANN, NIE WERDE ICH VERGESSEN,

die Opfer, die du mir gebracht.

Es wäre ja wohl sehr vermessen,

hätt’ etwas anderes ich gedacht.

IN WORTEN KANN ICH ES NICHT SAGEN,

was an Güte ich von dir erfahren.

Diese Schuld nun abzutragen,

ginge nicht in hundert Jahren.

SO LASS‘ UNS HEUTE UNSERN BUND ERNEUERN,

der in sich noch viel Schönes birgt.

Ein Blick nach vorn dient uns anzufeuern,

dass das Gewesene so auf uns wirkt.

* THINKING OF THE FUTURE, Henry’s last poem to Carin on January 17, 1994, their 35th anniversary of the day they met.

Biography Henry and Carin

1911 November 3: Henry born in Brussels, Belgium, to German-Jewish parents; father Hermann Marx, businessman from Siegelsbach, Baden; mother Martha, née Simonson, from Elberfeld, Rhineland

1916 Death of mother from pernicious anemia

1918-29 Return with father to Germany. 1918, Preschool in Heilbronn; 1920-26, Luitpold-Oberrealschule (secondary school), Munich; 1926-29, Goethe-Oberrealschule, Berlin

1929-33 Studies at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Berlin: Law, forensic medicine, and drama

1933 Termination of studies, since Jews are no longer permitted to take first State Examination. Literary and journalistic contributions to Berlin daily newspapers; radio broadcasting of lectures, dramas, and documentaries

1934 January to June: Apprenticeship at Arnhold-Bleichröder Bank, Berlin June 22: Arrest by the Gestapo; six weeks of “Protective Custody” at Columbia-Haus, Berlin, and in the concentration camps Oranienburg and Lichtenburg

1935-36 Employment at cigar factory of Heinrich Jacobi, Berlin; main task: Re-organization of sales districts 1937 Emigration to the United States. February 3: Arrival in New York; trip to Cuba to obtain immigration visa

June 1937 (until 1969): Member of editorial staff of German language paper New Yorker Staats-Zeitung & Herold, first as music, theater and film critic, later as editor-in-chief

1938 Marriage to Paula Loew

1939 May 23: Carin born in Strasbourg, France, second oldest daughter of Franz-Xaver Drechsler, chemical engineer, and Elfried, nee Möser, both ethnic Germans from Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia

-

1941 Birth of Claude Marx, only child of Paula and Henry Marx

1943 Death of Henry’s father, Hermann Marx, two years after his emigration to the United States September 24: Death of Carin’s father near the town of Zhitomir, Ukraine

1944 November: As Allied Forces approach Strasbourg, Carin’s mother returns to Sudetenland with her children

1945 Henry acquires American citizenship

February 45: Carin’s mother flees with three of her children from the Sudetenland to southern Germany

May 45: Coercion by the French occupation authority to return to Strasbourg. Our

mother’s refusal to go to Prague as a spy for the French government leads to our

imprisonment in the former concentration camp of Natzweiler-Struthof

November 45: Release from Natzweiler, and return to the town of Wolfegg in southern Germany

1952 Henry: Regular contributions for medical journals Ärztliche Praxis and Euromed, Munich, and Medical World News, New York

1953-56 Carin: Apprenticeship as Assistant for Business and Tax Advising in Bad Waldsee, Germany 1957: Family moves to district town Ravensburg

1954-59 Henry: Co-founder and Secretary of the German Theatre, Inc. in New York; Active participation in German language productions

1959 January: Carin moves to Munich; employment at CPA office in daytime; attends acting school at night

January 17: Carin and Henry’s first encounter on the way to the Cuvilliés Theater

1960 February: Henry publishes his first book: H3 in the Battle Against Old Age, Plenum Press, New York

November 3: Emigration Carin from LeHavre by ship to America

November 7: Arrival in New York

1961-64 Carin: Fine Arts studies at the School of Visual Arts, New York

1961-69 Henry: Active participation in German theater guest performances in New York: Deutsches Schauspielhaus, Hamburg (Goethe’s Faust), 1961; Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf (Lessing’s Nathan the Wise), 1962; Schiller Theatre Berlin (Schiller’s Don Carlos, Zuckmayer’s Captain of Köpenick), 1964; Bayerisches Staatsschauspiel (Büchner’s Woyzeck, Hauptmann’s The Rats), 1966; etc. Beginning of Henry’s contributions to Voice of America, RIAS Berlin, and German daily Die Welt. Henry enters the Goethe-Institut New York (German Cultural Institute) as head of the program department (until the end of 1975), then as theater and music consultant

1966 December 3: Birth of Katina, daughter of Carin and Henry

1967 August: Henry’s divorce from Paula Loew

October 6: Carin and Henry’s wedding day

1971 Daughter Katina attends United Nations School, New York (until high school graduation in 1984)

Carin: Transition from painting to photography; introductory courses at the New School for Social Research, New York

1972-76 Henry: Lectures at conferences on Theater in Exile at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin; on Subsidies of the Performing Arts in Berlin at Aspen Conference, USA, and organization of an international conference on the same topic in New York; conference of the Literary Colloquium, Cologne, on The America Image in Germany

Lectures at American colleges and universities on Players from Abroad, German Theatre in the United States, Berlin Cabaret of the Twenties. Organization of the Weill-Lenya exhibition at Lincoln Center, New York

Carin: Photo series in German newspapers and magazines; Sept/Oct 1976: SoHo

documentation (400 slides) at the Academy of Arts, Berlin

1978 Henry: Receives Federal Cross of Merit by German Government

1979-80 Carin, a Zen practitioner, undertakes extensive photo documentation of Dai Bosatsu Zendo, a Zen monastery in the Catskill Mountains, for book publication

1979-82 Henry: Secretary of the German-American Partnership Program (German-American student exchange)

Publication of travel guides New York and Washington, and San Francisco and Los Angeles,

Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart. Organization of Kurt Weill-Festival at Goethe House

New York

Elected Vice President of the Kurt Weill Foundation of Music, New York

1981: Accepts teaching assignment for summer semester at Cologne University,

Germany; lectures on Theater in America

Carin: Photo exhibition of documentary on the Bowery (the street of alcoholics and

the homeless in Lower Manhattan) at the Museum of the City of New York, and Goethe House New York

1983-85 Henry: Author of Germans in the New World (history of German-Americans),

Westermann Verlag, Braunschweig; The East Coast of the United States, and The South

West of the United States, both Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart; Editor of Erwin Piscator.

Letters from Germany, Prometh Verlag, Cologne

January 1985 (until his death): Editor-in-Chief of the weekly Aufbau, the only

German-Jewish paper in America

Carin: February/March 1985: Exhibition of Bowery photographs at Haus am

Kleistpark, Berlin. Publication of Bowery, Pictures of a Disreputable Street, Harenberg

Verlag, Dortmund, Germany

Katina: High School graduation from the United Nations School, New York (1984),

followed by anthropology studies at the New School for Social Research, New York

(1984-85), University of Freiburg, Germany (1985-88), and the University of Hawaii,

Honolulu (1989-90); Master’s Degree at UH (1994)

1986 Henry: Author of The Broadway Story (with series of photographs by Carin), Econ

Verlag, Düsseldorf

Lecture tour to Societies for Christian-Jewish Cooperation in Germany (Hamburg,

Munich, Bielefeld, Celle, Fulda, Bad Nauheim, Stuttgart, Ravensburg, Konstanz)

Carin acquires American citizenship

1988-91 Henry: Author of Baedeker California, Baedeker Verlag, Stuttgart; photographs by

Carin

Lectures: Theater and Drama in Exile, University of Hamburg; Reflections on Germany,

State Opera Berlin; Lecture tour through German cities on the theme The German

Jews in the United States

Carin: Publication of Ich liebe New York (I Love New York), Harenberg Verlag, Dortmund, 1988; Broadway (documentation of the longest Street in the world), Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1988; Aloha Hawaii, Paradise in the Pacific Ocean, Harenberg Verlag, Dortmund, 1991

1992 Henry (author), Carin (photographer) of the Harenberg City Guide New York, and

Baedeker Hawaii

Henry: Last lecture tour to Societies for Christian Jewish Cooperation in Hannover,

Wiesbaden, Görlitz, and Dresden

November: Occurrence of first symptoms of Henry’s AVM condition (arteriovenous

malformation, a mulfunction of arteries and veins)

1993 Henry: January-March: Hospitalization with surgery and rehabilitation, then

resumption of activity at the Aufbau

July: Participation in conference by the Kurt Weill Foundation in Santa Fe, New

Mexico

October/November: Recurrence of AVM disease; second surgery

December 29: Henry’s son dies of lung cancer

1994 Henry: Essay, Immigrant, Emigrant, Expatriate, Refugee: What am I? in Hoffnung America,

NWD-Verlag, Bremerhaven

Preliminary work on planned book German Jews in America for Bleicher Verlag, Stuttgart

June 6: Carin and Henry’s last mutual journey: A week-long stay in Berlin as part of the 25th anniversary of the Visitor Program for Persecuted and Emigrated Berliners. Henry holds last public speech at the opening of the program

June 14-18: Family reunion in Ravensburg

June 19: Arrival in Adelboden, Carin and Henry’s resort in the Swiss Alps. Henry

contracts pneumonia

June 21: Hospitalization at District Hospital Frutigen

June 22, 9:30 a.m.: Death of Henry at the District Hospital Frutigen

Contact Sheet

Comments

Elisabeth and Robert Kashey

Shepherd W & K Galleries, New York

“We are deeply touched by your book. The photographs and the text are truly wonderful.”

Michael Lahr

Executive Director, The Lahr von Leitis Academy & Program Director | ELYSIUM between two continents | New York, Munich, and Berlin

“Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.”

Dr. Markus Wessendorf

Chair, Department of Theatre and Dance, University of Hawaii, Honolulu

“Next to your photographs, I enjoyed the oral history-aspect of your book: your own family history interwoven with the biography of your husband – both joined by the camp experience, although from almost opposite perspectives of religion, class affiliation, “sophistication,” etc. I learned a lot not only about you, but indirectly also about the different prevailing circumstances in Germany and the United States after World War II.”

Louise Kerz Hirschfeld

Cultural Historian

“We are members of a relatively small group of women who devoted a portion of our lives to assuage the guilt of a generation of German premeditated brutalists. We set out to ease the suffering the criminals committed. Each in our own way . . . with true compassion and understanding for the physical and psychic damage these Jewish men encountered in their early lives. . . Your photographs, so honest, express interior vulnerability at the loss of a loved one . . . the constant widow’s veil and delicate composition of the photos almost resemble a body without life. Because death steals itself into both partners of a marriage. Your love story is beautifully told. Henry will be with you forever.”

Cynthia Wessendorf

www.manoadesignandtext.com, Honolulu, Hawaii

“I was overwhelmed with how beautiful your life story and photos are. It literally brought tears to my eyes. The fractured families and flights through Europe, the war, your resilience and bravery, the love story with Henry, your emergence as an exceptional photographer, the death and grieving process. . . this immense emotional story is told with spare words and images that cut through the noise and chaos of life and present the parts that matter most.”

Michael Drechsler, Berlin, Germany

African art collector and brother of Carin Drechsler-Marx

“The text in your beautiful book is thought-provoking, particularly the reflections on National Socialism and Judaism. Confronted with our family history and Henry’s prominent position in the Jewish community of New York, it sometimes seems as if by proxy – not only in the texts but also in your images – you had to shoulder the guilt of others.”

Verena Drechsler, Stuttgart, Germany

Niece of Carin Drechsler-Marx

“I am deeply impressed by your courage to confront your life with Henry and your grief so candidly. Your book is a small treasure. Through it I got to know you a lot better: vulnerable and strong at the same time.”